As enrolments in schools rise, it is time for India to invest in quality public education, says Harsh Mander

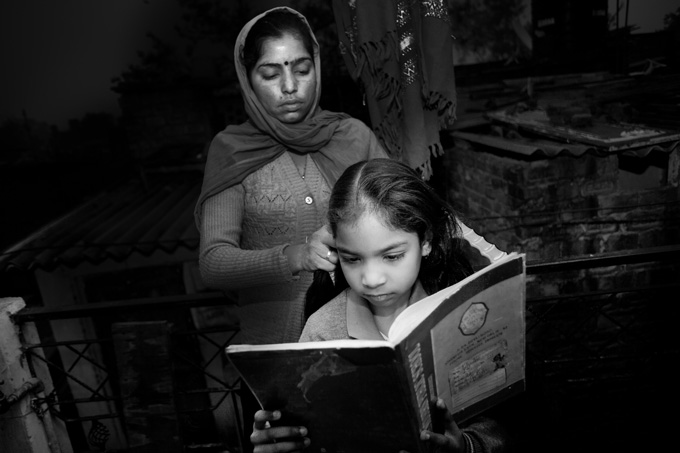

My work requires me to interact with some of the most dispossessed and impoverished communities in the country, and I consistently find that even as poor households battle hunger, debt, unemployment and social humiliation, most still send their children to school. They do this at enormous personal cost, and with great hope for what the schools have to offer. Rich or poor, most Indian parents now aspire to educate their children. An encouraging 96 percent of children aged 6-14 years are enrolled in schools today.

But sadly, schools betray these aspirations, as the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2012 suggests. The report gathers compelling and disturbing evidence of abysmal learning outcomes in a majority of schools across India. More than half the children in Class V cannot read a Class II textbook, and three-quarters of children in Class III cannot read a Class I textbook.

The wake-up call, which emerges from ASER 2012, is that the levels of reading and arithmetic in our schools are not only poor but also declining in many states. The situation is one of a “deepening crisis” in education, as Madhav Chavan, the author of the report notes. Only three states — Himachal Pradesh, Punjab and Kerala — have high learning levels on the ASER scale. Except Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, where levels are low but not falling, other big states contribute heavily to the overall declining learning levels.

The Right to Education Act (RTE) initially eliminated all forms of student evaluation, and laid down — for good reasons — that children will not be held back for poor performance. But this well-intentioned provision may have thrown out the baby with the bathwater, because it further reduced the accountability of the system for scholastic performance. Fortunately, this is now remedied because continuous and comprehensive evaluation is now a part of the law.

What RTE promises is a publicly funded school in the neighbourhood of every child in the country. But as the ASER survey reminds us, the biggest challenge to the public education system is not only to expand the reach of government schools, but to improve their quality. RTE tends to equate quality education with the qualifications of teachers. It mandates formal training for every teacher, assuming that this will improve the quality of education. It fails to acknowledge that teachers will teach well in environments where they are valued, supported with imaginative teaching materials, their skills continuously upgraded, and robust systems of monitoring and accountability established.

Scholastic outcomes are poorer in government schools, compared to private ones. But as Chavan admits, “Private school education is not great and the socio-economic educational background of children’s families, parental aspirations and additional support for learning contribute majorly to their better performance. Yet, the fact remains that the learning gap between government and private school students is widening. This widening gap may make the private schools look better, but in an absolute sense it is important to note that as of 2012 less than 40 percent of Class V children in private schools could solve problems in division.”

Parents are despairing of the public school system, and opt for lower-end private schools. The report estimates that 35 percent of children enrolled in schools study in private institutions. If the current trend sustains, more than half our children would be paying for their education by 2020.

The solution is not to accept privatisation of education. Children studying in government schools will be the poorest, and if the quality of education continues to decline, it will confine the poor to the boundaries of socio-economic barriers established by their birth. The country needs to invest significantly more in government schools, in the salaries, and training of government teachers. India needs to show that it believes in securing equal chances for all children, regardless of the accident of where they are born. This is possible only with a dynamic and effective public school system.